Collision Over the Grand Canyon: How a 1956 Disaster Transformed Airspace—and Exposed the Need For Federal Oversight

The 1956 Grand Canyon plane crash was the biggest aviation disaster in American history at the time

Just past 9 a.m. on a bright morning on June 30, 1956, two commercial airliners—Trans World Airlines (TWA) Flight 2, a Lockheed Super Constellation, and United Flight 718, a Douglas DC-7—took off from Los Angeles International Airport, three minutes apart and bound for Kansas City and Chicago, respectively.

The flight paths of both planes were scheduled to cross, but at different times and at an altitude difference of 2,000 feet.

However, after requesting and receiving permission to deviate from its flight path to avoid thunderheads, TWA Flight 2 climbed to an altitude of 21,000 feet—the scheduled altitude of United Flight 718.

Both planes approached the Grand Canyon, flying at nearly identical speed and at the same altitude. In order to adhere to regulations that required them to remain clear of—and above—clouds, both pilots were likely maneuvering around the area’s large cumulus clouds.

About an hour and a half after they took off, at 10:31 a.m., the planes collided midair above the canyon’s towering red cliffs.

The crash killed all 128 people aboard both aircraft, becoming the deadliest aviation disaster in U.S. history at the time.

Scattered across the remote, rugged terrain of Grand Canyon National Park, the wreckage shocked the nation—not just for its scale, but for where it happened: in the skies above one of America’s most cherished public lands.

The aftermath of the collision would lead to sweeping federal reforms. It directly spurred the creation of the Federal Aviation Agency (now the FAA) and ushered in a new era of centralized, coordinated airspace management. But the legacy of the 1956 crash also extends beyond aviation.

It stands as a stark reminder of the consequences of under-regulated public resources—and the vital role of federal oversight in protecting both people and places we all share.

A Disaster Above One of America’s Crown Jewel Parks

At 10:31 a.m. on June 30, radar and communication technology were still in their infancy. Air traffic controllers had little visibility over uncontrolled airspace, and pilots were often left to visually navigate around weather and other aircraft.

In addition to that, it was also common—and permitted at the time—for commercial airline pilots to make maneuvers to provide passengers with a better view of the Grand Canyon.

Besides the presence of thunderclouds, which reduced visibility, a potential Grand Canyon detour by one—or both—of the aircraft, which would have slowed it down, may have contributed to the fatal midair collision.

The accident instantly gripped the nation’s attention. The victims included families, tourists, and business travelers. The remote crash site complicated recovery efforts and some pieces of the wreckage remain in the Grand Canyon to this today.

Two memorial sites were established for both aircraft’s victims. Many of the TWA victims are interred at Citizen’s Cemetery in Flagstaff, Arizona, while many of the United victims are buried at the Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery within Grand Canyon National Park.

The fact that the tragedy occurred over a national park added a layer of symbolism. Grand Canyon National Park—established in 1919 after having been a national monument for eleven years—represented the heart of America’s public lands legacy.

Now it became the site of a haunting example of what can happen when shared resources are left without adequate safeguards.

A Wake-Up Call for the Skies

In the wake of the crash, public outrage demanded action. Congressional hearings quickly revealed just how outdated and fractured U.S. air traffic control systems were.

The Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA), then overseeing commercial aviation, lacked sufficient radar coverage, had limited authority over military airspace, and could not guarantee safe separation between aircraft in uncontrolled zones.

By 1958, the response was clear. Congress passed the Federal Aviation Act, creating the Federal Aviation Agency to centralize and modernize U.S. airspace regulation.

The new agency introduced radar-based air traffic control nationwide, and standardized pilot communication and navigation protocols.

The reforms were a turning point in the federal government’s role in overseeing not just transportation infrastructure, but the shared systems—like airspace and public lands—that all Americans rely on.

Federal Stewardship: From Airspace to Earth

The parallels between the skies and the lands below are striking.

Just as the 1956 crash revealed the dangers of a fragmented aviation system, it also underscored the need for careful federal management of public spaces—with well-funded programs and systems, as well as by trained, educated, professional, and dedicated staff.

The Grand Canyon, with its soaring vistas and rugged wilderness, was not just scenery—it was part of a growing vision of what public resources could be when protected from commercial exploitation and managed for the greater good.

This idea resonates today.

National parks, forests, wildlife refuges, and other public lands are facing intense pressure from overcrowding, climate change, and legislative threats—particularly budget cuts, reduced educational programs, staff layoffs, privatization, increased resource extraction, and a general disregard for science.

The 1956 disaster reminds us that unregulated, fragmented systems, whether in the air or on the ground, eventually break down—with consequences that affect us all.

Commemorating a Tragedy, Preserving a Legacy

Today, the crash site near the canyon’s eastern rim remains remote and mostly inaccessible, though commemorations have increased in recent years.

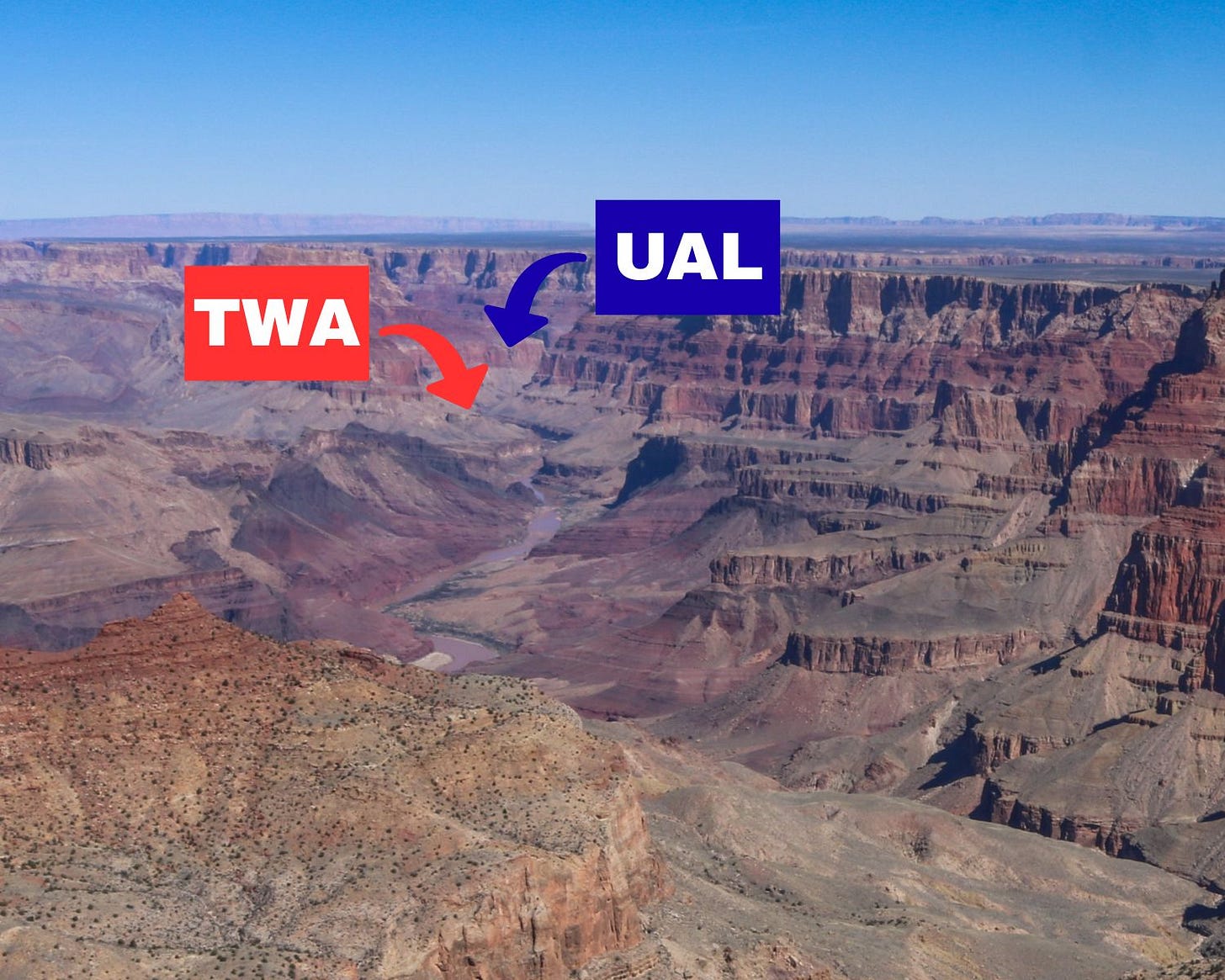

A plaque and stone memorial have been installed at Desert View Watchtower to honor the victims and commemorate the horrific crash. You can actually see the places where both places crashed from Desert View.

Additionally, he skies above Grand Canyon are now far more regulated.

The FAA and National Park Service jointly manage airspace to reduce noise pollution, protect wildlife, and preserve the wilderness experience. Quiet technology requirements and no-fly zones are part of a broader movement to manage aerial tourism over public lands.

These efforts reflect the lasting legacy of the 1956 collision: not only the modernization of air travel, but a deeper understanding that public spaces require active, informed, and professional regulation and stewardship.

A Lesson for the Future

As we mark the 69th anniversary of the Grand Canyon disaster, the lessons are as relevant as ever. Our public lands and resources—be they forests, rivers, or the airspace above—are only as safe and accessible as the systems we build to protect them.

When those systems fail, the cost can be measured in lives, ecosystems, and national trust.

The midair collision of 1956 was not just an aviation accident.

It was a turning point in the American relationship with federal oversight, infrastructure, and public lands—remember that its the park rangers who lead, assist with, and/or carry out search-and-rescue and recovery efforts.

It helped usher in an era of safety and regulation in the skies and served as a reminder that even the most majestic landscapes are not immune to tragedy.

The Grand Canyon, etched by time and shaped by rivers, now holds within it the memory of a modern catastrophe—and the enduring responsibility to never let it happen again.

Watched a doc on that recently. So amazing to think about the skies being so relatively empty back then