From Mississippi Woods to Toy Store Shelves: The Moral Legacy of the Teddy Bear

How Theodore Roosevelt's conscience and compassion created America's favorite toy.

At first glance, the teddy bear is a simple childhood object—a fuzzy, stitched bundle of comfort tucked into cribs, packed for sleepovers, and clutched tightly during thunderstorms.

But behind this plush icon lies a profound and surprisingly political origin story, one that offers a powerful reminder of how public decency, restraint, and moral courage once defined American leadership.

In a cultural moment when character feels in short supply, it’s worth revisiting how, of all things, a stuffed bear came to symbolize something much bigger.

A Hunting Trip in Mississippi

The year was 1902. The month was November. President Theodore Roosevelt, known for his unrelenting vigor, expansive ego, and love of the outdoors, had been invited by Mississippi Governor Andrew Longino on a hunting trip in Mississippi.

The main goal was to settle a boundary dispute, but it was also meant to offer Roosevelt—a famously avid hunter—some sport.

As a passionate big game hunter and former Rough Rider during the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt was eager to break away from politics, head into the outdoors, and bag a bear. The hunt, however, wasn’t going well.

After days without success, his guides—led by renowned African American hunter Holt Collier, and eager to please the President—captured, beat, and tied a young black bear to a tree, inviting Roosevelt to fire the shot.

Roosevelt refused. He was appalled. He called the act unsportsmanlike. Though he ordered the bear be put down mercifully due to its injuries, Roosevelt made it clear he wouldn’t sully the chase with such a hollow “victory.”

The scene might have ended there, remembered only by a few hunting companions and written up in local newspapers.

A Political Cartoon

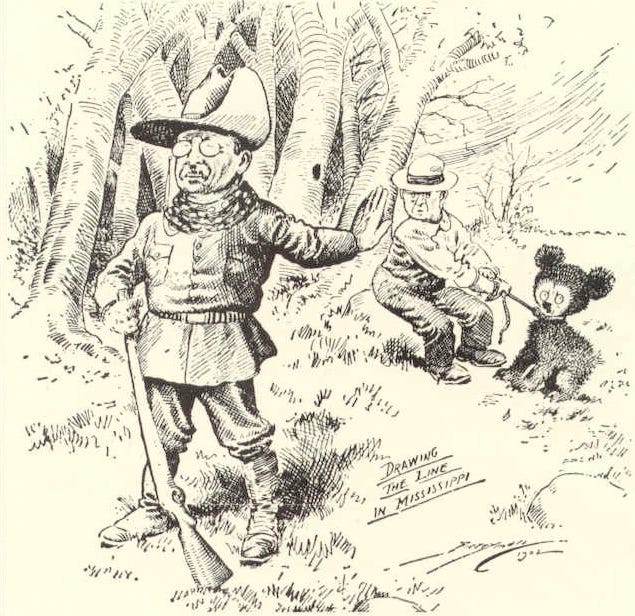

Instead, the incident caught the attention of Clifford Berryman, a political cartoonist for The Washington Post.

In a drawing titled “Drawing the Line in Mississippi,” published on November 16, 1902, Berryman depicted Roosevelt turning away from a frightened, cowering bear cub, rifle lowered, hand raised.

It wasn’t just a cute visual gag—it was a metaphor for fairness, dignity, and the ethical limits of power.

That cartoon struck a national chord. It softened the image of the famously brash Roosevelt, giving the American public a glimpse of compassion and principle beneath the bravado.

The bear—innocent and wide-eyed—became a character in its own right, symbolizing something universal: the instinct to protect the vulnerable, even when no one is watching.

A Business Opportunity

Enter Morris Michtom, a Russian Jewish immigrant who ran a small candy and toy shop in Brooklyn, New York.

Inspired by Berryman’s cartoon and the buzz surrounding Roosevelt’s gesture, he and his wife Rose hand-stitched a small plush bear cub and placed it in their store window with a sign that read “Teddy’s Bear.”

The toy was an instant sensation.

After securing Roosevelt’s reluctant permission to use his name, the Michtoms began producing more bears and eventually founded the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company—one of the earliest American toy manufacturers.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, in Germany, the Steiff company—founded by Margarete Steiff, a seamstress who had overcome polio—was developing its own line of plush bears with movable limbs.

Her nephew, Richard Steiff, designed a jointed stuffed bear in 1902, unaware of the Roosevelt story. When Steiff bears were displayed at the 1903 Leipzig Toy Fair, an American buyer ordered thousands, cementing the toy’s popularity on both sides of the Atlantic.

By 1906, the term “teddy bear” had become widespread. It was a rare case of a toy named after a sitting president—and even rarer, one embraced by the public and the namesake alike.

Roosevelt, who disdained being associated with frivolity, nonetheless accepted the teddy bear’s fame, often using it in political imagery and promotional items.

A Cultural Symbol

It’s tempting to chalk this all up as a happy accident of history: a president, a cartoon, a clever merchant, and a boom in plush toy production. But that narrative sells short the deeper meaning of the teddy bear’s origin story.

Roosevelt’s decision that day in Mississippi wasn’t calculated or politically expedient. He didn’t take a poll or consult an image consultant. He acted from a place of internal code—an instinct about fairness, about sportsmanship, and about what it means to hold power without abusing it.

That action, captured and mythologized by artists and entrepreneurs, became an enduring cultural symbol.

The teddy bear is cuddled by toddlers and treasured by collectors not just because it’s soft, but because it carries an unspoken message: compassion matters. How we treat those with less power—be they animals, children, or the disenfranchised—says everything about who we are.

In today’s world, the contrast is striking. We now live in an era where cruelty is sometimes branded as strength, and decency as weakness. Leaders mock empathy as “woke” and equate morality with political liability.

Public figures dodge accountability, while tone and image override action.

Against that backdrop, Roosevelt’s simple refusal to shoot a helpless bear feels almost radical.

A Crucial Lesson

The teddy bear reminds us that doing the right thing, especially when no one demands it, still matters. And it underscores that values aren’t just abstract ideas—they ripple outward into art, commerce, and culture.

A moment of integrity on a hunting trip helped birth a multibillion-dollar industry, foster generations of comfort objects, and inspire children worldwide.

There’s a special irony in all this.

Theodore Roosevelt, who would go on to help found the U.S. Forest Service and protect over 230 million acres of public lands—including 5 national parks, 18 national monuments, 51 federal bird reserves, and a mindboggling 150 national forests—is better known in many households today not for his conservation legacy, but for a stuffed animal.

Yet perhaps that’s not such a bad thing.

After all, the teddy bear distills what Roosevelt believed in—respect for nature, ethical boundaries, and the notion that strength need not come at the expense of mercy.

The bear also became a platform for storytelling and emotional resilience. Children learned to express empathy through their teddy bears. They dressed them, talked to them, and leaned on them during lonely nights.

Psychologists have since recognized such toys as “transitional objects,” helping children move from dependence to autonomy. In a way, the teddy bear is a soft ambassador of moral development.

And so here we are, more than 120 years later, living in a very different America, but one still scattered with teddy bears in bedrooms, hospitals, and—ironically considering the teddy bear’s roots in empathy, ethics, and moral restraint—in immigration detention centers.

They continue to serve as companions during trauma, tools in therapy, and emblems of comfort in war zones. Charities distribute them to children fleeing disasters. Police carry them in squad cars for children experiencing domestic violence.

Their utility may be symbolic, but their impact is real.

We need more teddy bear moments today—instances when leaders act not for gain, but from a deeply rooted sense of right and wrong.

We need more public figures who would rather draw a moral line than take the easy shot. And we need reminders that ethical action, however small, can still shape the world.

It’s easy to forget that behind even the humblest cultural icons lie choices—real, human decisions that ripple through time. The teddy bear isn’t just a toy. It’s a parable. One about restraint in the face of easy victory. About how cartoons and immigrants and presidents can together create something beautiful. About how compassion, when put into action, can last a century or more.

So the next time you see a teddy bear—maybe on a child’s shelf, or at a thrift store, or clutched in tiny hands during a storm, perhaps even in the arms of a refugee child—remember this: its roots are tangled not in fluff, but in character.

And maybe, just maybe, there’s still time to bring that kind of conscience back into our public life.