Murder in the Mangroves: How Feathers, Fashion, and Firearms Culminated In One of America's Strongest Wildlife Protection Laws

Guy Bradley's death helped solidify wildlife protection in the United States

On July 8, 1905—120 years ago today—a single gunshot cracked through the sweltering Florida air. It echoed across the sawgrass marshes and over the tangled mangroves of the Everglades.

The bullet struck 35-year-old Guy Bradley—warden, frontiersman, and naturalist—fatally wounding him as he attempted to arrest plume hunters slaughtering birds for their feathers.

In that instant, the Everglades lost its first true guardian.

But the death of Guy Bradley would mark the birth of something far greater: a national reckoning with the bloody price of fashion, and the emergence of the American conservation movement as a moral force.

Bradley wasn’t just a casualty of the wilderness. He was its sentinel, its interpreter, and its defender in an era when the Everglades were still viewed more as swamp than sanctuary.

Today, with Everglades National Park hosting over 700,000 visitors annually and serving as a refuge for countless endangered species, it’s worth remembering that none of it came easily—and that conservation in America has always carried with it a human cost.

The Wild South: Plume Hunters and the Price of Fashion

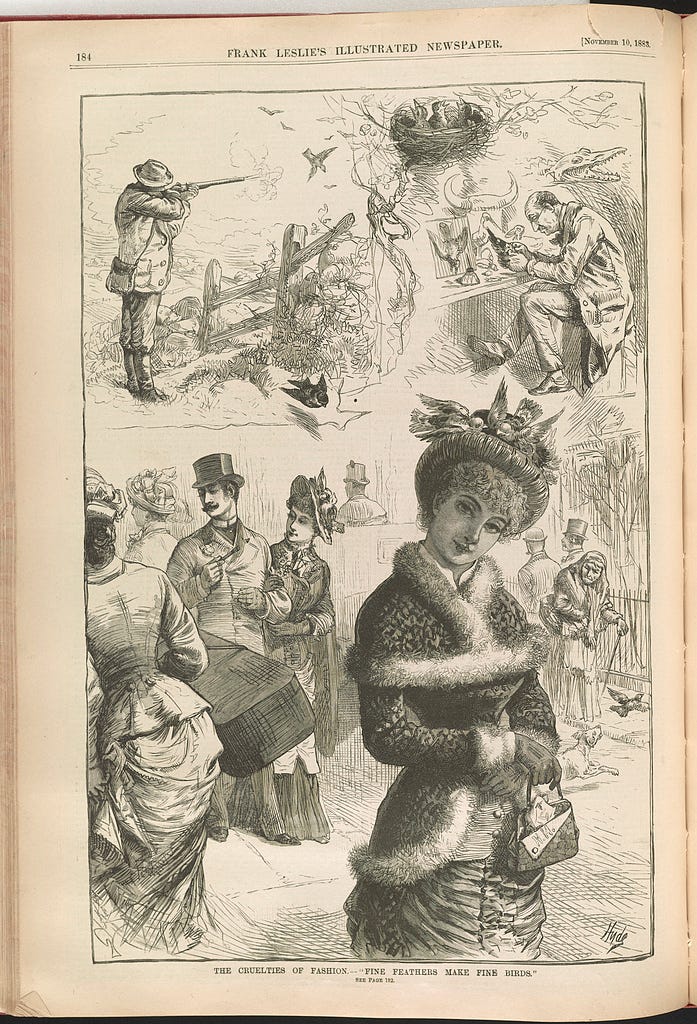

At the turn of the 20th century, women’s hats in New York, London, and Paris were adorned with elaborate feathers, wings, and sometimes even entire bird carcasses—symbols of elegance and status.

The fashion industry’s appetite for feathers was insatiable. Especially wading birds like egrets, herons, ibis, and spoonbills were hunted in staggering numbers. Plume hunters prowled rookeries in the Everglades, decimating bird populations during breeding season when mothers nested helplessly beside their chicks.

At one point, an ounce of egret plumes was worth twice that of pure gold.

The slaughter was indiscriminate. Hunters shot hundreds of birds in a single day—five million a year—leaving chicks to starve and eggs to rot. With each nest destroyed, two generations were lost. Wildlife refuges did not yet exist. There were no park rangers. No Endangered Species Act.

Only men like Guy Bradley, armed with little more than a badge and a boat, stood between the Everglades’ birds and extinction.

Born in Chicago in 1870, Bradley had grown up on the frontier of Florida. He was intimately familiar with the tangled, unforgiving landscape of the southern Everglades.

Like many young men in the area, Bradley was originally a plume hunter himself. But unlike most, after witnessing the destruction caused by the so-called “Feather Wars,” he had a change of heart.

As sentiment began to shift—thanks in part to the work of conservationists like George Bird Grinnell and women like Harriet Hemenway and Minna Hall of the Audubon Society—Bradley became one of the first federal game wardens appointed to patrol the Florida Keys and coastal Everglades.

But the job, both game warden and deputy sheriff, was perilous. Bradley was paid a meager salary of $35 a month and tasked with patrolling hundreds of square miles alone, from the Ten Thousand Islands through Flamingo, and all the way to Key West.

His adversaries were often desperate, heavily armed, and deeply resentful of government interference. Many had grown up believing nature was there for the taking. When Bradley tried to stop them, they threatened him. And finally, they killed him.

July 8, 1905: A Shot in the Sawgrass

On that fateful day, Bradley found three men shooting cormorants just a couple of miles from his home in Flamingo. As he approached their skiff, he was shot and left for dead in his small boat. His body was found the following day, having drifted about ten miles from the crime scene.

The shooter—Walter Smith, the leader of a notorious plume-hunting family—claimed self-defense and was eventually acquitted. Smith and one of his sons had previously been arrested by Bradley, likely intensifying the animosity.

The killing shocked the nation. The New York Times, Forest and Stream, and other major publications covered the story extensively. The Audubon Society decried the failure of the courts. Artists painted portraits of Bradley. Schoolchildren sent letters of support.

He became a martyr to a cause that was only just beginning to coalesce.

To the people of Florida, Bradley’s death exposed the moral cost of inaction. To the nation, it showed that conservation required not only ideals, but enforcement, courage, and sacrifice.

The Legacy of a Fallen Warden

Bradley’s death catalyzed the wildlife protection movement. Though his killer eventually went free, public outrage helped push forward a suite of reforms that would soon change the face of conservation.

Two years before Bradley’s murder, President Theodore Roosevelt had established Pelican Island—also in south Florida—as the nation’s very first federal bird refuge, the predecessor of the current sprawling Wildlife Refuge system. Roosevelt would go on to create dozens more bird reserves after Bradley’s death.

In 1910, the Audubon Plumage Act was passed by New York lawmakers, effectively making the plume trade illegal. Many more states followed their example.

In 1913, the Weeks–McLean Act banned the spring shooting of migratory birds.

And in 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act—one of the strongest and most enduring pieces of American wildlife legislation—was passed, protecting hundreds of species from commercial slaughter.

The Everglades itself was gradually recognized for its ecological richness.

The national park would not be formally created until 1947, thanks to the work of people like Marjory Stoneman Douglas. But Guy Bradley’s name was already etched into its lore. There’s a sense that the park itself is his true memorial.

Today, the wonderful 1-mile Guy Bradley Trail parallels the shore of Florida Bay, connecting the Flamingo Campground and the visitor center, which is officially named in his honor—Guy Bradley Visitor Center.

Additionally, a relatively large key just south of Flamingo has been named Bradley Key to commemorate his life and dedication to the birds of the Everglades. It’s the nearest key to Flamingo and an excellent destination for an afternoon paddling trip.

A Wilderness Still in Peril

Over a century after Bradley’s death, the threats to the Everglades remain as urgent as ever. Rising sea levels, polluted runoff, invasive species, and political indifference have all taken a toll on this unique subtropical wilderness.

Florida panthers, manatees, and snail kites still cling to existence. Restoration efforts—some of the most complex environmental projects in U.S. history—are ongoing, but underfunded and often politicized.

What would Guy Bradley make of the modern Everglades?

He might marvel at its designation as a World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve. He might weep at the loss of water flow and the creeping salt intrusion. He would likely still recognize it as a battlefield—less violent, perhaps, but no less vital.

The Conservation Hero America Forgot

Bradley’s story deserves more than a footnote. In many ways, it embodies the American environmental struggle: a lone figure confronting overwhelming odds. A confrontation between extractive tradition and ecological stewardship. A tragedy that catalyzed reform.

His life illustrates that conservation isn’t just about species and scenery—it’s about values, law, sacrifice, and courage.

He died trying to enforce laws that had no teeth, facing adversaries emboldened by indifference. Today’s wardens and rangers face eerily similar threats—low pay, double shifts, political hostility, dangerous conditions.

We celebrate their work on posters and in visitor centers, but we fail to fund their missions adequately. We place the burden of conservation on their shoulders, while gutting the legal and financial tools they need to succeed.

A Call to Remember

Guy Bradley’s legacy reminds us that the defense of nature is not always bloodless.

He is considered to have been the first true American game warden—and the first one to die in the line of duty. His death helped birth a movement. And yet, his name is rarely mentioned alongside Muir, Roosevelt, Grinnell, or Leopold.

That silence is telling. Americans are comfortable celebrating poets of the wilderness—but less so its enforcers. But without both, the national parks would be fiction.

Without Bradley, perhaps the Everglades would be little more than farmland, suburbs, or the massive jetport it was once designed to become, drained and paved over, its great white egrets, green herons, and roseate spoonbills extinct and forgotten.

You can read more about Guy Bradley’s life and legacy in Stuart B. McIver’s book Death in the Everglades: The Murder of Guy Bradley, America’s First Martyr to Environmentalism.