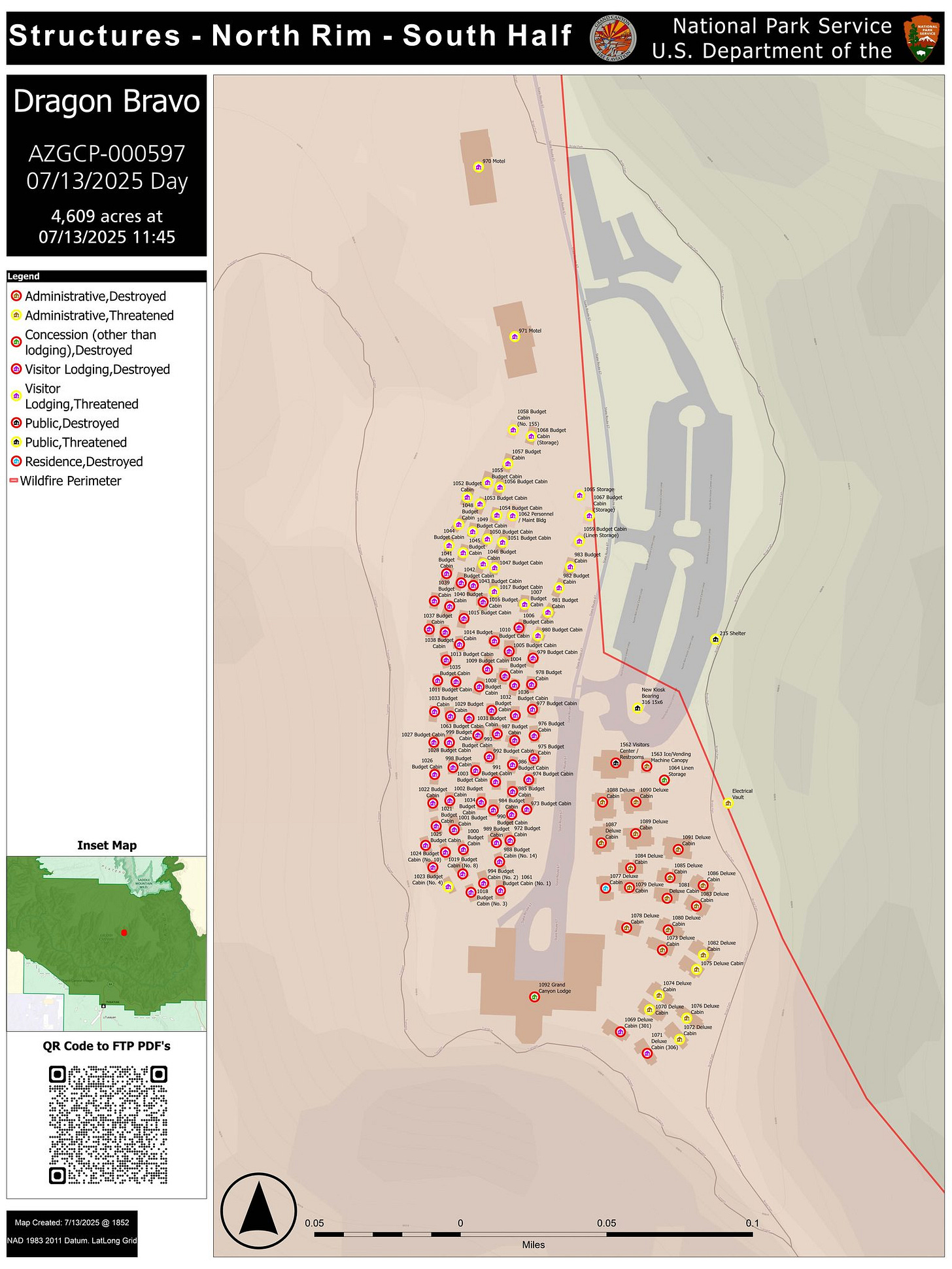

On July 13, the historic Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim burned to the ground.

A century-old icon—once described as America’s “best front porch”—is now ash, charred rock, and twisted metal.

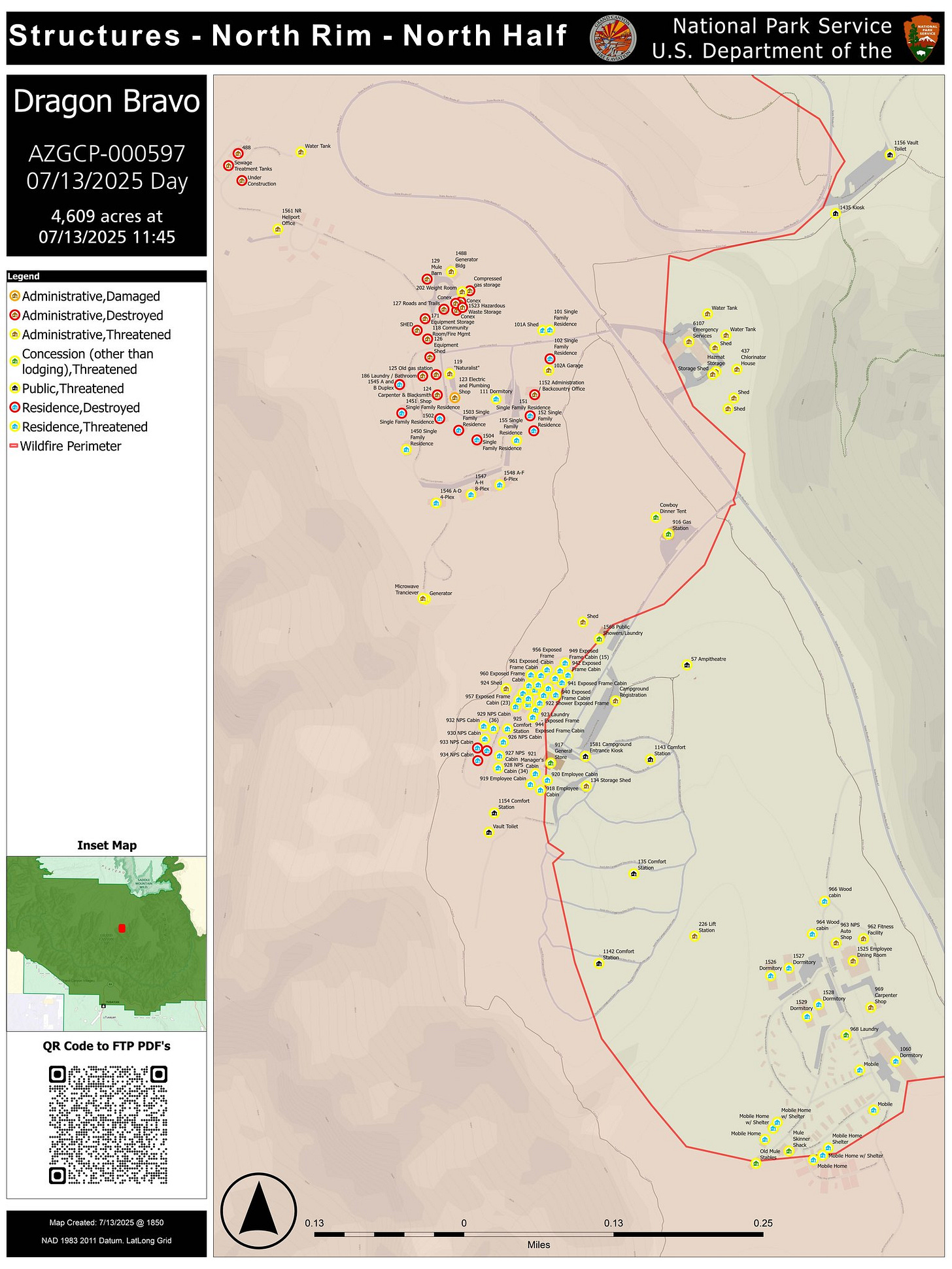

More than 50 structures in Grand Canyon National Park were destroyed, including beloved cabins, staff housing, and the North Rim’s water treatment plant.

The North Rim is closed for the season. The Dragon Bravo Fire, sparked by lightning on July 4, has now scorched more than 8,500 acres and is still burning at 0% containment.

And we are left with a single question: How did this happen?

The destruction of the Grand Canyon Lodge is not just a tragedy. It’s a sign.

It’s a warning about what happens when land management is starved of funding, staff, communication, and expertise. What happens when climate change goes unaddressed, and when political leaders treat fire as an “act of God” instead of a systemic failure of preparation and policy.

This wasn’t an unavoidable catastrophe. This was a foreseeable crisis.

In its early days, the Dragon Bravo Fire was just ten acres. Park officials opted to “confine and contain” it—a legal form of full suppression that allows a fire to burn within designated boundaries.

This strategy, used appropriately, can effectively reduce excess fuel loads, support ecological health, and minimize long-term fire risk.

These types of so-called “controlled burns” are common practice in winter and spring, implemented to create areas that could stop future fires from spreading.

But this time, during the hottest part of the Arizona summer, the fire could neither be confined nor contained. It couldn’t be controlled.

By July 11, winds gusted to 40 miles per hour and the fire had roared past containment lines. Temperatures soared, humidity plummeted, and the Grand Canyon’s North Rim—a remote place with spotty cell service and limited access—was suddenly under siege.

Then came the disaster within the disaster: the water treatment plant ignited, releasing a plume of chlorine gas that forced firefighting crews to stand down and hikers in the inner canyon to be evacuated.

By the morning of July 13, the iconic Grand Canyon Lodge was gone.

Also destroyed are the North Rim visitor center, the gas station, dozens of historic cabins, administrative offices, and employee housing facilities—for a total of 50 to 80 structures lost.

This is not just about one fire, or one major building. It is about a pattern of neglect and short-term thinking that has left our national parks increasingly vulnerable for years, if not decades.

The Grand Canyon Lodge, a National Historic Landmark, was more than a place to sleep. It was a link to the legacy of 20th-century park architecture—crafted from stone and timber to blend seamlessly into the rim’s geology.

Generations watched sunrises from its glass-walled Sun Room, enjoyed a glass of wine on the porch at sunset, felt the humbling silence of the canyon below, and understood in that moment what the word “awe” really meant.

Now it is gone. And serious questions are being raised right away.

Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs has now called for an independent federal investigation. So have Senators Mark Kelly and Ruben Gallego. Their questions are urgent and valid.

Why was a controlled burn strategy pursued in July, during peak tourist season, with known high winds forecast? Why weren’t more resources staged in advance? Why weren’t vulnerable structures better protected?

“An incident of this magnitude demands intense oversight and scrutiny into the federal government’s emergency response. They must first take aggressive action to end the wildfire and prevent further damage. But Arizonans deserve answers for how this fire was allowed to decimate the Grand Canyon National Park,” Governor Hobbs said.

The National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) also released a statement, praising the efforts of park staff while emphasizing the consequences of chronic underfunding and understaffing.

“As the fires continue to burn, we feel the weight of the devastating loss of the North Rim’s irreplaceable natural and historic resources, including the Grand Canyon Lodge,” said Sanober Mirza, Arizona Program Manager at the NPCA. “The destruction of buildings, including residential housing, is a profound tragedy that has left many North Rim residents without their homes and belongings.”

“We are deeply grateful no lives were lost, as park staff quickly and safely evacuated visitors from at-risk areas in the canyon and along the North Rim. Park staff are the stewards of this iconic national park, and they demonstrated their critical role in caring for the park and its visitors every single day, even in crisis.” Mirza said.

“This heartbreaking moment underscores the importance of fully funding and staffing our national parks now and for future generations. As wildfires and other disasters increase in frequency and intensity, parks need the proper resources to manage them.”

For years, NPCA and other watchdogs have warned that the National Park Service is stretched dangerously thin.

The agency manages over 85 million acres with significantly fewer staff than it had in 2010. Fire management teams are underpaid, overworked, and often rely on temporary seasonal hires.

Maintenance backlogs exceed $20 billion. Communications infrastructure is outdated. And the North Rim—open just six months a year—is often treated as an afterthought when it comes to resources.

Is it any wonder that a “managed” fire grew into a historic disaster?

The backdrop to all of this is climate change. The West is hotter, drier, and windier than ever before. Fire seasons start earlier and last longer. Fuels ignite faster. Storms produce more lightning.

The Dragon Bravo Fire is one of several active blazes burning in northern Arizona right now. These are not “acts of nature” in the traditional sense. They are the direct results of a warming world and a political failure to adapt.

Regardless of the cause of a fire—in this case, a lightning strike—the manner and speed of the response matter. On-the-ground readiness matters. Local decision-making, training, and emergency response coordination matter. And in this case, all were overwhelmed.

Why exactly this got so out of control will be determined by investigations.

But to prevent something like this from happening again, we must go beyond post-mortems. What we need—desperately and urgently—is a new national strategy.

The Grand Canyon Lodge was one of the last true survivors of a time when national parks weren’t overcrowded and a visit, even to a major park like Grand Canyon, was peaceful, contemplative, and reinvigorating.

As Will Pattiz from More Than Just Parks said so perfectly, “[i]t was one of the last remaining park lodges from the National Park Service rustic era. Nothing about it felt modern. That was the point.”

“For nearly a century, it offered something no other lodge in the park system could match - quiet. The South Rim gets all the crowds and the postcards. But the North Rim was where people went to disappear for a few days. To sit on the porch in the cold. To wake up and see the canyon glow gold at sunrise. To let the silence do its work.”

This all disappeared overnight, the result of a naturally caused wildfire managed as a “controlled burn” in the middle of the scorching Arizona summer.

The Grand Canyon Lodge will not be rebuilt overnight. Nor should it be, without a sober reckoning about how to protect the places we still have. As wildfires become more extreme, park design, construction materials, firefighting readiness, and visitor education must evolve.

Funding should increase, not decrease. Additional staff should be hired, not fired. Expertise should be valued, not ignored. Scientific research should be promoted, not reduced.

We need permanent firefighting staff at all major parks, especially those with known wildfire histories. We need modern equipment and hazard pay for wildland firefighters. We need smarter building codes for historic and non-historic structures alike. And we need political will to ensure that funding keeps pace with risk.

I would also like make sure that we voice our gratitude to all park rangers and firefighters who have been, and still are, working to combat the Dragon Bravo Fire, as well as other fires in the region.

Luckily, there have been no fatalities, which is thanks solely to the heroic actions of dedicated park staff.

The North Rim of the Grand Canyon will remain closed for the remainder of the 2025 season. Additionally, all inner canyon campgrounds and trails are also closed until further notice, including:

North Kaibab Trail and South Kaibab Trail

Bright Angel Trail below Havasupai Gardens

Phantom Ranch and Bright Angel Campground

River Trail between Pipe Creek and the South Kaibab

Tonto East between Havasupai Gardens and Tip Off

All backcountry and canyoneering routes stemming from the North or South Kaibab, or the Bright Angel Trail

River runners are not permitted to stop at Boat Beach, but may continue to Pipe Creek Beach for exchanges

The Grand Canyon Conservancy has set up a “Grand Canyon Disaster Relief Fund,” which you can find here. All donations will go directly to:

Helping North Rim residents who have lost their homes and belongings;

Meeting critical needs that arise as the situation on the North Rim evolves; and

Supporting the long-term restoration and recovery of the unique North Rim landscape.

This isn’t just about the Grand Canyon, though. This is about Black Canyon of the Gunnison, which is currently battling its own out-of-control fires and is closed entirely.

This is about Yellowstone and Yosemite. About Rocky Mountain, North Cascades, Everglades, and Shenandoah and all the places that define the American landscape.

If we do not invest in them—fully, consistently, and urgently—we will lose them, one front porch at a time.

Congress is debating its Fiscal Year 2026 Budget as we speak and this is the time to contact your senators and representatives.

In a draft bill released just a few days ago, the House’s Appropriations Committee proposed a $176 million cut to the operations budget of the National Park Service. Although this is less severe than the gigantic $900 million cut proposed by the Trump administration, it’s a cut nonetheless—not a much-needed budget increase.

It also includes a $37 million cut (21%) cut to the Park Service’s construction budget.

If implemented, this would make it even more difficult—practically impossible—for the agency to reduce its deferred maintenance backlog and upgrade or repair crucial facilities, including, as of last weekend, the Grand Canyon Lodge.

It’s a bill that attacks conservation and promotes pollution and fossil fuel extraction, which—as the scientific consensus has been for decades—directly contributes to climate change, which, in its turn, results in increasingly powerful and uncontrollable wildfires like the Dragon Bravo Fire in Grand Canyon National Park.

According to Defenders of Wildlife, the House’s draft bill also includes significant cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and numerous other provisions that would negatively affect wildlife conservation and the environment in general.

For example—and this is just a selection of what it would do—it would:

Block all funding for listing the greater sage-grouse and for implementing the new range wide plans to conserve the species;

Delist the gray wolf;

Delist the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzly bear population;

Block funding to protect the wolverine;

Block funding to protect captive fish under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), such as sturgeon;

Block funding to reintroduce grizzly bears to the North Cascades;

Block funding to reintroduce grizzly bears to the Bitterroot ecosystem;

Promote continued expansion of offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska; and

Mandate issuing at least four onshore oil and gas lease sales in any state where land is available, including Wyoming, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Nevada, and Alaska.

To help protect our parks, park rangers, wildlife, and the environment, the National Parks Conservation Association has several actions you can take.

You can easily use this form to tell Congress to fully fund and staff our national parks, improve management practices, and allow the NPS to use cutting-edge climate science to prevent and/or manage disasters like wildfires, floods, and storms.