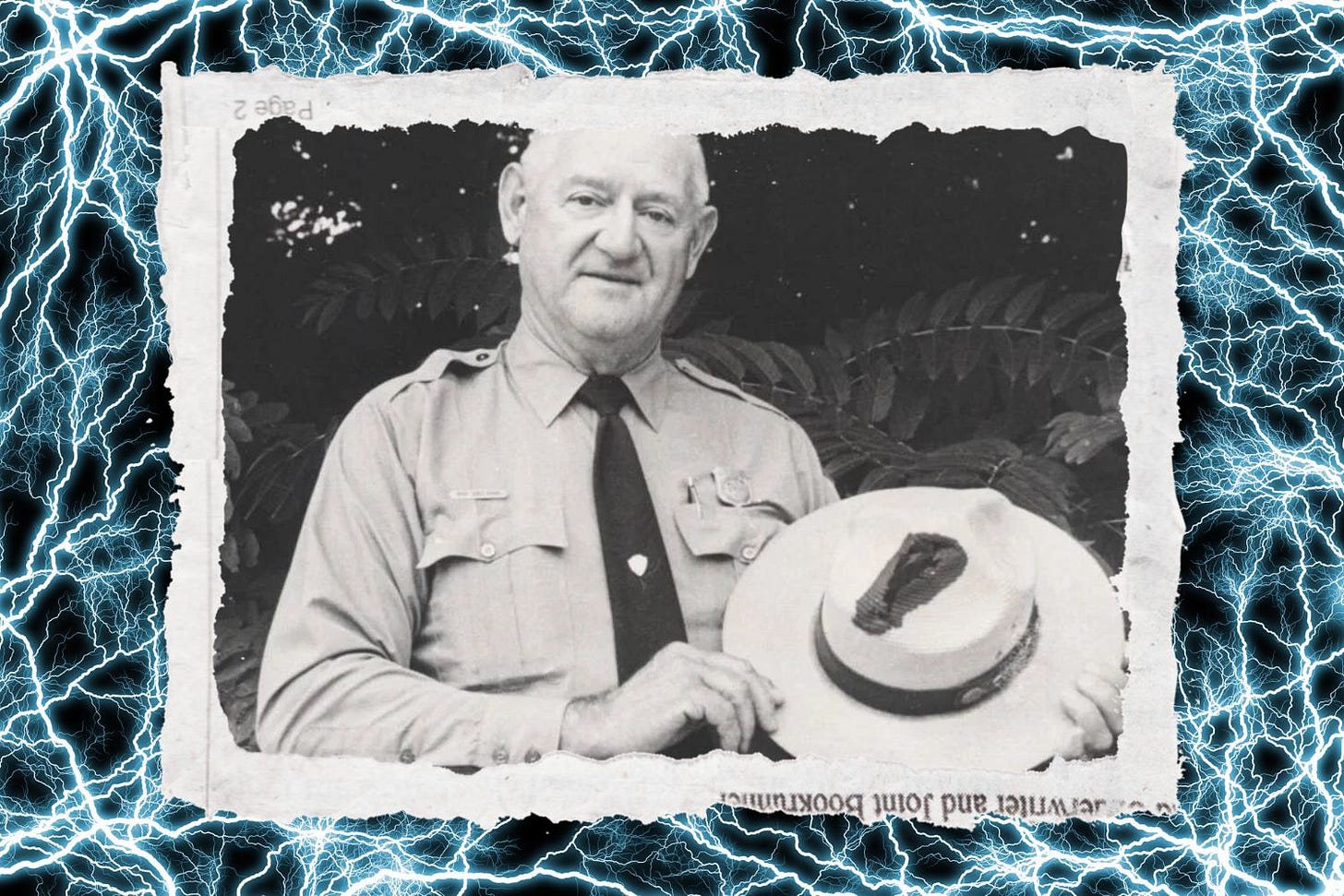

The "Spark Ranger:" The Strange, Stoic Life of Shenandoah's Roy Sullivan, Human Lightning Rod

Park ranger Roy Sullivan was struck by lightning seven times, surviving all of them—still a Guinness World Record

In the pantheon of America’s park rangers, few names strike a chord of intrigue like that of Roy Cleveland Sullivan.

Known around the world as the man struck by lightning more times than any other human in recorded history—the last strike occurring 48 years ago today, on June 25, 1977—Sullivan is often remembered for the bizarre statistical anomaly of his life.

But beyond the folklore of his electrifying encounters lies a deeper story—one of quiet duty, mental resilience, and a lifelong devotion to the wilderness of Shenandoah National Park.

What Roy Sullivan embodied is something Americans too often ignore: the inner lives and emotional sacrifices of the public servants who tend our wild places.

In a moment when the meaning and future of public lands are once again up for political negotiation, Sullivan’s story is a quiet rebuke to indifference. It is also a reminder that we owe more than applause to the people who live their lives in service to the landscapes we claim to revere.

A Ranger's Calling

Born on February 7, 1912, in Greene County, Virginia, Roy Sullivan grew up in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains. He joined the National Park Service in 1940 and would spend most of his 36-year career patrolling Shenandoah National Park.

Described by colleagues as deeply competent, reserved, and even a bit shy, Sullivan was the quintessential ranger: a steward of the land, a first responder, and a solitary figure threading his way through the highlands of one of the East Coast’s most rugged landscapes.

The terrain of Shenandoah is notorious for its unpredictable weather, which only adds to the strange credibility of Sullivan’s story.

Between 1942 and 1977, he was struck by lightning seven separate times—a feat so improbable that it landed him a place in the Guinness World Records. That record still stands to this day.

But unlike the carnival myth such a story might suggest, each strike was carefully documented, often with hospital records and physical evidence.

The Lightning Strikes

Sullivan’s first known lightning strike occurred in 1942, when he was trapped in a fire lookout tower during a storm.

The tower was newly built and had no lightning rod; it was struck multiple times, setting it ablaze. Sullivan ran out and was struck just as he left the tower, leaving him with a burned leg and the first of what would become a long series of encounters with nature’s most unpredictable force.

Subsequent strikes followed in bizarre, almost cinematic ways:

In 1969, while driving his truck through the park, lightning struck nearby trees and leapt through the open window.

In 1970, he was struck in his front yard.

In 1972, while working inside a ranger station.

In 1973, while patrolling the park and observing a storm from a safe distance.

In 1976, while checking on a campsite.

And on June 25, 1977, while fishing, he was struck again—the seventh and last time.

Each strike left its mark: burned eyebrows, a lost big toenail, hair loss, and persistent burn injuries. One even set his hair on fire.

After the fourth strike, Sullivan began keeping a jug of water in his car to put out the inevitable flames. Despite all this, he returned to work each time.

The Stoicism of Survival

What makes Roy Sullivan's story so remarkable is not just the lightning, but how he responded to it. Rather than seek attention, he sought solitude. Rather than quit, he kept patrolling.

His continued dedication to his duties as a park ranger, even as he became something of a local legend, speaks to a deeper character trait: a stoic, almost transcendental relationship with nature.

He never considered himself cursed. He believed lightning “seeks you out” but refused to let it define him. Sullivan once noted, with dry irony, that after the third strike, he noticed a pattern: storms seemed to follow him. He began to develop an almost mystical understanding of storm behavior, sensing atmospheric changes before others did.

There is a deeper dimension to Sullivan’s story, one that reveals itself only if we look past the spectacle.

Being struck by lightning so many times didn’t just harm him physically—it took a psychological toll. It isolated him.

He reportedly feared social gatherings and declined social invitations, worried that lightning would find him in the company of others. He became increasingly withdrawn. The emotional toll of being seen not as a man but as a walking freak occurrence began to weigh on him.

A Tragic End

Roy Sullivan retired from the National Park Service in 1976. Though his lightning encounters had made him a minor celebrity, his post-retirement life was quiet and, ultimately, tragic.

In 1983, at the age of 71, Sullivan died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. His wife later remarked that he had been deeply lonely and tired of the myth that had come to define him.

What Sullivan Can Teach Us About Public Lands

In an age where national parks are strained by underfunding and budget cuts, climate change, overcrowding, and political neglect, Roy Sullivan’s story takes on new weight.

Rangers today face wildfires, floods, and shrinking staff. And yet, like Sullivan, they keep showing up.

Why? Because public lands matter. Because wild places deserve stewards. And because somewhere deep in our national identity is a belief—often unrealized, often unspoken—that these lands connect us to something larger than ourselves.

But that belief is meaningless without people like Sullivan to make it real. Rangers don’t just guide tours and issue permits. They perform rescues. They monitor wildlife. They maintain trails. They represent the living infrastructure of our collective reverence.

And too often, they do so anonymously—not for fame or money, but simply because they care.

Sullivan’s real story, stripped of lightning bolts, is one of daily devotion.

It’s the kind of legacy we should honor not just in tribute videos or quirky trivia books, but in policy: in funding ranger housing, increasing salaries, improving mental health support, and safeguarding the profession from political whims.

The Legacy of Roy Sullivan

Today, Roy Sullivan remains a footnote in pop culture—an oddity, a quiz question, a human lightning rod. But he deserves far more. His legacy is not only about lightning strikes but about resilience, duty, and the hidden emotional costs of life on the margins of myth and wilderness.

He reminds us that park rangers are more than guides or guardians. They are often isolated individuals who serve as sentinels of remote landscapes—bearing the storms, both literal and figurative, that most of us never see.

Sullivan didn’t ask for lightning. But he walked through fire, again and again, and kept doing his job.

In that, he represents the enduring spirit of America’s park rangers: dedicated, humble, passionate, hard-working, and worthy of respect.

Help support park rangers by sending a message to Congress via this convenient pre-written form by the National Parks Conservation Association.