UNESCO Again Flags Everglades National Park as “In Danger”—While First Detainees Arrive at ‘Alligator Alcatraz’

Everglades National Park has been on UNESCO's "in danger" list since 2010 due to sea level rise, invasive species, and pollution

The United States currently has 26 UNESCO World Heritage Sites—natural and/or cultural places of global significance.

No fewer than 19 of those are managed by the National Park Service, including iconic parks like Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Hawai‘i Volcanoes, Redwood, Great Smoky Mountains, and Olympic.

Now, at its 47th session in Paris, which is still ongoing, the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has once again sounded the alarm on one specific park: Everglades National Park.

UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee formally reaffirmed the park’s place on the List of World Heritage in Danger.

It cited escalating threats, particularly climate change and associated rising sea levels, invasive species, water pollution, and urban encroachment—conditions that greatly imperil one of the planet’s most unique wetland ecosystems.

Despite incremental improvements, the Committee concluded that Everglades National Park, a World Heritage Site since 1979 and on the “in danger” list since 2010, continues to fall short of recovery benchmarks.

These include not only scientific thresholds for hydrology and biodiversity but also broader environmental goals long associated with the Everglades’ restoration roadmap.

Stuck in Recovery Limbo

The U.S. government’s own conservation update, submitted to UNESCO on December 5, 2024, showed mixed progress.

While 14 of 63 ecological indicators showed signs of improvement, the majority remained static or declined. Nearly one-third are currently listed as being “of significant concern.”

Among the encouraging developments are improved freshwater flows and the return of wading birds like herons and egrets to coastal nesting grounds. American crocodile numbers are also rising, a sign of expanding estuarine habitat—which, while good for the crocodiles, is a direct result of rising sea levels.

But those gains are overshadowed by a host of serious problems.

Mercury and methylmercury levels remain high, threatening wildlife via bioaccumulation. The roseate spoonbill, once an indicator species, has abandoned historic nesting areas, likely due to freshwater decline and sea level rise.

Climate change, meanwhile, is not just a looming threat—it’s an active force altering the landscape. Marsh collapse, vegetation die-offs, and saltwater intrusion into interior wetlands are already happening.

The park has launched a three-year process, including “brainstorming workshops,” to develop a formal climate change adaptation strategy, both in the short term and long term. However, UNESCO says stronger action is urgently needed.

“In Danger” Since 2010—And Counting

UNESCO’s decision to keep Everglades National Park on the List of World Heritage in Danger extends a designation that has been in place continuously for 15 years. The park had previously appeared on the list from 1993 to 2007 due to similar concerns.

This international scrutiny reflects just how slow progress has been in undoing the decades of hydrological damage inflicted by canals, levees, development, and agriculture throughout South Florida.

UNESCO praised the National Park Service and U.S. Department of the Interior for recent gains, especially in water management and wildlife monitoring. But the Committee stressed that achieving full recovery will likely take “several decades,” and called for a reassessment of outdated corrective measures, many of which date back to 2006 and 2011.

It also called for a new joint monitoring mission to help evaluate next steps, especially in light of ongoing litigation around the controversial SR 836/Dolphin Expressway extension—a road that critics say would destroy sensitive wetlands crucial to the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP).

Environmental Fears Rise Over “Alligator Alcatraz”

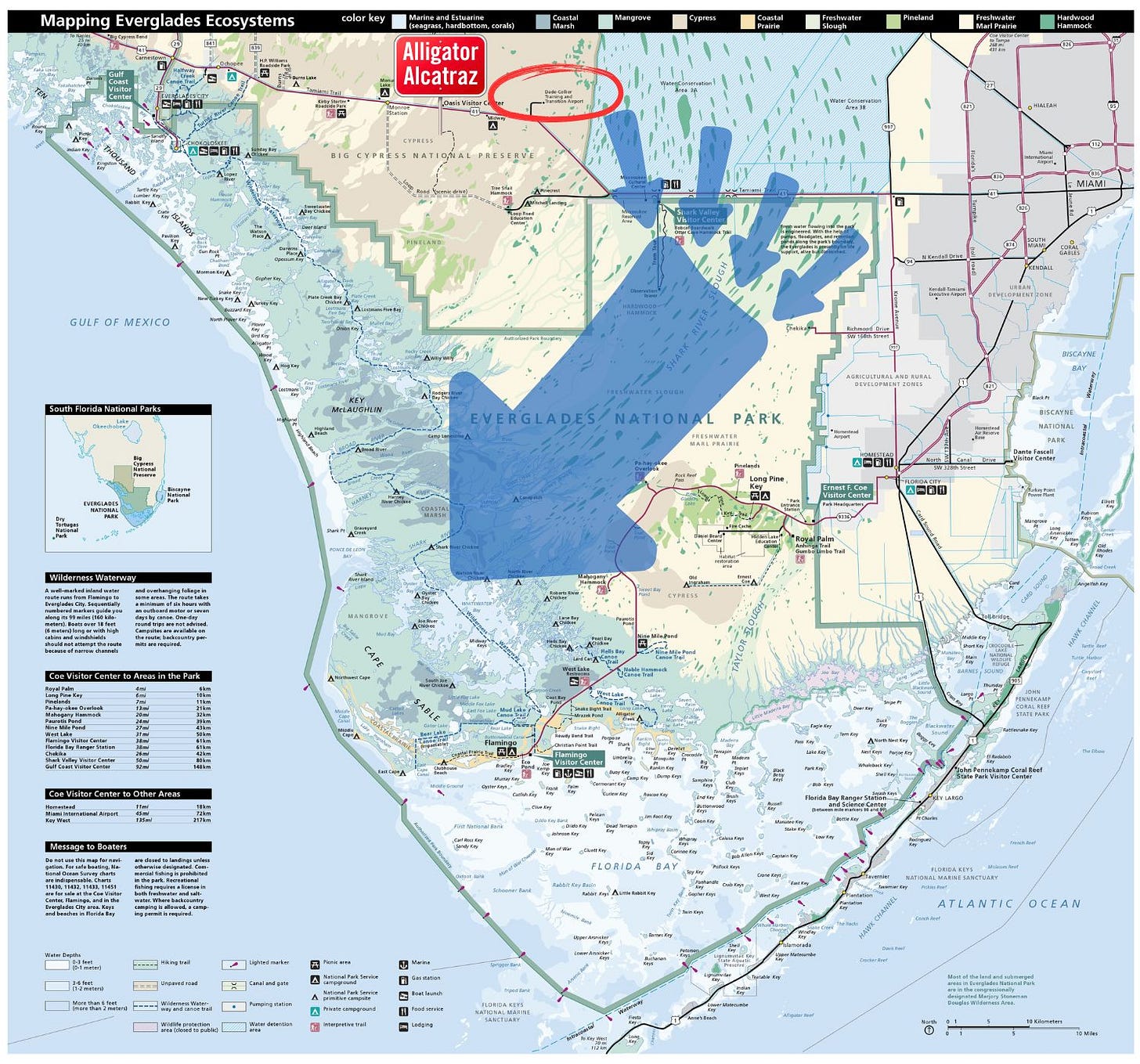

At the same time that UNESCO is calling for greater environmental vigilance, a deeply controversial development has emerged just outside Everglades National Park: the construction of a massive immigrant detention facility nicknamed “Alligator Alcatraz.”

Located on the site of the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport—which was once on track to become a gigantic commercial airport—the detention center lies within the boundaries Big Cypress National Preserve, also a National Park Service site, and near the northern Everglades National Park boundary.

It’s planned to house thousands of detainees in a remote area of Florida’s subtropical wilderness, home to alligators, invasive pythons, and many millions of mosquitoes.

Critics have blasted the plan as both an affront to human rights and a direct environmental threat to the fragile Everglades ecosystem.

The project site sits within the Everglades watershed and is surrounded by habitat essential for species like black bears, snail kites, wood storks, American alligators, and the endangered Florida panther.

Activists warn that the center would fragment migration corridors, increase stormwater and wastewater runoff, and strain local water supplies—all in an area already suffering from hydrological degradation.

“This massive detention center will blight one of the most iconic ecosystems in the world. This reckless attack on the Everglades—the lifeblood of Florida—risks polluting sensitive waters and turning more endangered Florida panthers into roadkill. It makes no sense to build what’s essentially a new development in the Everglades for any reason, but this reason is particularly despicable.” - Elise Bennett, Florida and Caribbean director and attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity

A Symbol of Conflicting Priorities

“Alligator Alcatraz” has quickly become a flashpoint in Florida’s ongoing battle between development and conservation. It represents a confluence of two of the state’s most volatile debates: immigration policy and environmental protection.

And for many, the proposal starkly contradicts the goals of the $10 billion Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, which aims to return natural water flows and protect biodiversity. It’s the largest hydrological restoration project in the history of the United States.

The detention facility, which is already in operation, comes with new roadways, increased vehicle traffic, and intensive utility infrastructure, including bathrooms and the daily trash and waste produced by up to 5,000 detainees and staff—all of which push deeper into wildlands that federal and state agencies have spent decades trying to preserve.

The project mirrors other looming threats, such as the SR 836 extension, which UNESCO has warned could “negatively impact wetlands set aside for restoration.”

“The site is more than 96% wetlands, surrounded by Big Cypress National Preserve, and is habitat for the endangered Florida panther and other iconic species. This scheme is not only cruel, it threatens the Everglades ecosystem that state and federal taxpayers have spent billions to protect. Friends of the Everglades was founded by Marjory Stoneman Douglas in 1969 to stop harmful development at this very location. Fifty-six years later, the threat has returned—and it poses another existential threat to the Everglades.” - Eve Samples, Executive Director of Friends of the Everglades

What’s at Stake

At risk is not just the park’s UNESCO status but the ecological health of the greater Everglades—an interconnected mosaic of swamps, sloughs, and estuaries that supports iconic wildlife and delivers clean water to more than eight million people in South Florida.

If climate-driven collapse and invasive development—such as the extremely politically motivated “Alligator Alcatraz” detention center—continue unchecked, what’s lost will be far more than a prestigious UNESCO World Heritage label.

The “in danger” designation may not carry legal force, but it is a red flag to the international community—and an embarrassment to America’s conservation policies.

It signals that even as the world watches, the very future of the Everglades hangs in the balance—and appears to be no more than an afterthought. A mass prison for immigrants is not helping that cause.

UNESCO has requested an updated conservation report from the U.S. by December 1, 2026, and urged an updated monitoring mission well in advance. Whether that means halting road projects or scrapping prison plans is unclear.

But one thing is certain: the Everglades remains gravely endangered, and every decision made on its fringes has local, national, and global consequences.

Finally, I’d also like to point out that a particular type of infrastructure at “Alligator Alcatraz” may put another globally significant designation at risk.

Big Cypress National Preserve, within which the detention center is located, is an International Dark Sky Park—a place that has virtually no light pollution and, as such, a pristine “nighttime environment.” Getting that status is pretty difficult and keeping it is subject to very strict requirements.

Prison lights in Big Cypress National Preserve are all but certain to affect the park’s once-world-class night sky.